St. John Paul II—Marriage is Oriented to Eschatological Hope

In the catechesis widely known as the Theology of the Body, John Paul II speaks of marriage in a manner that is perfectly consonant with the language that is typically used by the tradition. Yet, there is also a way of speaking of marriage that he employs that directly links marriage to the eschatological fulfillment to which each and every person is ordered. In Audience 101—situated in the context of his discussion of the sacrament and the redemption of the body—John Paul speaks of sacramental marriage as being “fulfilled and realized in the perspective of the eschatological hope.”[1] To the uninitiated, this could come off as a rather curious statement when viewed in contrast with the celibate life, which is more often considered through an eschatological lens in light of the person’s final end.

Optatum totius, the decree on priestly training, echoes the perennial teaching of the Church on the value of this practice, stating that while “the duties and dignity of Christian matrimony” are to be acknowledged and honored, there is a clear hierarchy between it and “the surpassing excellence of virginity consecrated to Christ” (OT, §10). In renouncing the companionship of marriage, those who choose this state of life “bear witness to the resurrection of the world to come” (OT, §10).

In fact, it was John Paul himself who stated the following concerning communities of consecrated virgins: “they constitute a special eschatological image of the Heavenly Bride and of the life to come, when the Church will at last fully live her love for Christ the Bridegroom” (Vita consecrata, §7). So what are we to make of this? Could John Paul have simply changed his mind in the 15 years that passed between his statement in one of the Wednesday audiences and the promulgation of this apostolic exhortation? The answer lies, of course, in making the proper distinctions. While the state of virginity is spoken of as properly eschatological, matrimony is spoken of in terms of being perfectly fulfilled “in the perspective” of eschatological hope; in other words, matrimony is ordained for this life (as Christ himself tells us in the Gospel), but is fulfilled in light of that true marriage between Christ and the Church that virginity images in a more radical way.

Ultimately, the value of marriage as image of Christ and the Church finds its roots in divine revelation, as Paul’s words to the Ephesians interpret the text of Genesis: “‘a man shall leave his father and mother and be joined to his wife, and the two shall become one flesh.’ This is a great mystery, and I mean in reference to Christ and the Church” (Eph 5:31-32). The eschatological perspective is imbedded deep within this text, as the words of John the Seer will make clear at the end of the book of Revelation: marriage is a mystery which is directly related to the union of Christ and the Church, who will be joined once and for all in the great wedding feast of the Lamb, the true marriage from which each earthly union draws its name.

Bernard Lonergan on the Thomistic Synthesis

The last voice with which I would like to engage before looking directly at the novel which has given this essay its title is that of Bernard Lonergan. In what seems to me to be a rather overlooked work of his, Lonergan proposes what I find to be an extremely satisfying synthesis between the traditional doctrine of marriage as being primarily ordered to the procreation and education of children, and the modern emphasis on the mutual good of the spouses. I am speaking of an essay entitled “Finality, Love, Marriage,” published in the journal Theological Studies in 1943.

In this essay he means to offer a number of thoughts on what he calls the “recent fermentation of Catholic thought on the meaning and ends of marriage,” an interesting note, writing as he is 25 years before Humanae vitae and nearly 40 years before the Wednesday audiences on the Theology of the Body.[2] Without blunting the eloquence of Fr. Lonergan’s argument, and in an attempt to condense the overall scheme of the essay, what he has to say is this: the procreation and education of children is a “horizontal end” (in Lonergan’s terminology), and is more essential; the ascent of love participated by the spouses in friendship and charity is a “vertical end,” and is more excellent. In his own words:

[The] horizontal finality to procreation and education of children is more essential than the vertical finality to personal advance (sic) in perfection; and if we take the terms “primary” and “secondary” in the sense of more and less essential, we have at once the traditional position that the primary end of marriage is the procreation and education of children. Further, our less essential vertical finality corresponds at least roughly with the traditional secondary ends of [mutual help] and [the honorable remedy for concupiscence].[3]

In a single stroke Lonergan has united the realms of nature and grace in a manner that harmonizes the traditional and contemporary emphases on the good of marriage.

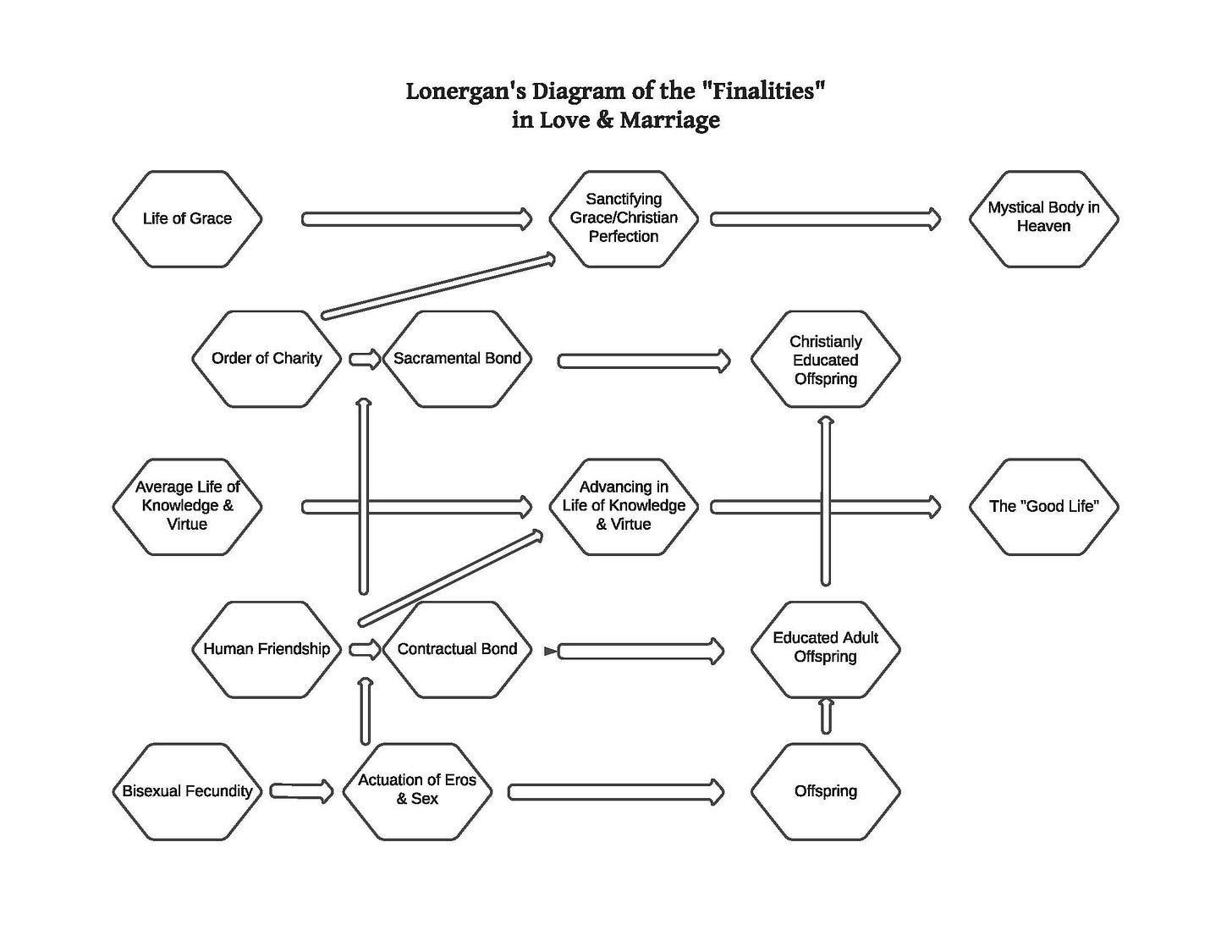

In the body of the essay Fr. Lonergan uses a complex chart to illustrate these various finalities:

In the structure and flow of the chart, we see horizontal arrows that clearly manifest that which is most essential: sexual fertility is ordered to the end of offspring, the ordering of existence to the good life, etc. The vertical thrust of the order of finalities indicates the manner in which the natural ordering of human goods is elevated to greater heights in the order of grace: the actuation of eros and sex is elevated into the sacramental bond of matrimony, and the result of bearing offspring is ordered towards their being educated in the truths of the Christian faith. The absolute finality of course is to the Beatific vision and the participation in God in the mystical body of Christ, to which all things (horizontal and vertical) are ordered.

This of course is a metaphysical and systematic outworking of the biblical data given most starkly in the book of Revelation. The whole purpose of Scripture, if we return to the mind of St. Thomas, is to lead to eternal life, and the Apocalypse contains the final culmination of this purpose by revealing the end to which we are brought: “Blessed are those who are called to the marriage supper of the Lamb” (Rev 19:9). As Aquinas notes, this nuptial feast is the final goal of salvation history—and thus, all of Scripture—as it concludes, in his words, “with the bride in the chamber of Jesus Christ, sharing in the life of glory, to which Jesus Christ himself leads us.”[4] This is the essence of Lonergan’s notion of “absolute finality,” by which the working of grace draws all things “further up and further in,” to quote a different work of Mr. Lewis.

The Beautiful Reality of Marriage in “That Hideous Strength”

In the wake of the preceding theoretical explorations, it seems wise to turn now to the illustrative. I began this essay by referencing the riddle which the revivified Merlin puts to Dr. Ransom, concerning the “cold marriages” of those who share in Earth’s curse of fallen nature. It would not be hyperbole, in my estimation, to say that it is marriage which holds the whole of the novel together. The novel opens with Jane Studdock, a disaffected newlywed doctoral candidate, reflecting on her own “cold marriage” as she has suddenly found herself at home and alone while her husband is consumed with his new appointment at Bracton College. Finding herself unable to concentrate on the completion of her doctoral thesis (a study of John Donne’s anthropology), she muses on the fact that her marriage is not quite what she expected it to be:

“Mutual society, help, and comfort,” said Jane bitterly. In reality marriage had proved to be the door out of a world of work and comradeship and laughter and innumerable things to do, into something like solitary confinement. For some years before their marriage she had never seen so little of Mark as she had done in the last six months… While they had been friends, and later when they were lovers, life itself had seemed too short for all they had to say to each other. But now… why had he married her? Was he still in love? If so, “being in love” must mean totally different things to men and women. Was it the crude truth that all the endless talks which had seemed to her, before they were married, the very medium of love itself, had never been to him more than a preliminary? (p. 1).

Her husband’s absence is keenly felt in a time that should be experienced as a period of joy and fulfillment, where the friendship and love that they had cultivated over a number of years could be finally enjoyed in an intimate union as their bond of love is ratified by the vows of marriage. Instead, Jane is a forgotten woman.

We will quickly come to find, however, that the fault lies equally on the shoulders of both husband and wife; as we are slowly invited into the lives of the Studdocks, we see that Mark has forsaken the duties of a husband in favor of advancing his own career just as Jane has attempted to break free from what she believes to be limiting constraints imposed on the fairer sex by patriarchal and misogynistic cultural tendencies. What had begun well enough, at the level of attraction, friendship, and eros had stagnated in a mire of apathy and resentment; competing goals and disparate ideas fueled by a toxic mix of prolonged absences and contraceptive encounters.

Without spoiling the major arcs of the story, I think I can safely say that Mark spends the vast majority of the novel attempting to enter deeper into the “inner circles” composed by the various faculty members and administrators of the college and the NICE (the National Institute of Coordinated Experiments), always seeking to be let in on greater secrets, and into greater confidences of those around him. Thankfully, contemporary academia has moved beyond anything so ridiculous. Once the true intentions of the secret society with which Jane’s husband has been so enamored are revealed, however, the couple hit rock bottom; they are in different ways shocked out of their myopic complacency and given new eyes to see the dignity of the other in a way that we could only call respectful awe. In the midst of the events which will serve as the climax of the novel, Mark is cast into a dim, damp cell and left in fear of his life where the final scale falls from his eyes:

He was aware, without even having to think of it, that it was he himself—nothing else in the whole universe—that had chosen the dust and broken bottles, the heap of old tin cans, the dry and choking places. An unexpected idea came into his head. This—this death of his—would be lucky for Jane… She seemed to him, as he now thought of her, to have in herself deep wells and knee-deep meadows of happiness, rivers of freshness, enchanted gardens of leisure, which he could not enter but could have spoiled…. She was not like him. It was well that she should be rid of him (pp. 244-45).

What makes Mark Studdock such an easy mark for the puppet masters of the NICE is the fact that much of the dehumanization that would be required on their part to fashion him into a fitting instrument for their nefarious deeds has already begun in Mark himself. Though there are layers upon layers of intrigue and duplicity at Belbury, the basic aims of the NICE are nothing less than the annihilation of human nature. It is gnosticism, it is demonic, which their cooperation with the macrobes demonstrates beyond a shadow of a doubt.

The wounds which Mark and Jane bear in their very selves, and which chafe within the bonds of their marriage, are similarly dehumanizing; they have dehumanized and instrumentalized one another in their fears and their desires. Their journey back to one another is a journey both of self-discovery—a recognition of their own wounds—and of healing and rehumanizing; it is ultimately a journey characterized by hope in the goodness of the other. We see the consummation of this hope (pun intended…) in the closing lines of the novel when Mark and Jane are reunited in the lodge under the protection of Venus, who has set all creation into a kind of Edenic rapture

Conclusions

Unfortunately, what I have been able to offer here has been only the vaguest of outlines. Any reader would be richly rewarded by reading (or rereading) Lewis’ novel with these thoughts in the back of their mind. In the final scene, we are with Jane and her thoughts as she makes her way to the lodge where she will find her husband waiting:

And Jane went out of the big house… into the liquid light and supernatural warmth of the garden… down to the lodge, descending the ladder of humility… she thought of her obedience and the setting of each foot before the other became a kind of sacrificial ceremony. And she thought of children, and of pain and death. And now she was halfway to the lodge, and thought of Mark and of all his sufferings.

At last, Jane has been purged, and is able to view her reality and her future with objectivity—the possibility of children, the inevitability of suffering and death—and in all this she is still capable of looking on her spouse with empathy and love.

Rather than looking upon marriage as a contest to be won or lost—in which case every marriage is lost—both Mark and Jane have begun in the end to view marriage in the spirit in which it was given. In the words of John Paul: “marriage is assigned to the spouses as an ethos… marriage is the place of the encounter of eros and ethos, and of their reciprocal interpenetration in the ‘heart’ of man and woman, and likewise in all their reciprocal relations” (TOB, 101.3).

[1] John Paul II, Man and Woman He Created Them: A Theology of the Body, trans. Michael Waldstein (Boston, MA: Pauline Books & Media, 2006), p. 525.

[2] Bernard Lonergan, “Finality, Love, Marriage,” in Theological Studies 4.4 (1943), 477.

[3] Lonergan, “Finality, Love, Marriage,” 507.

[4] Aquinas, Hic est liber.

[5] C. S. Lewis, That Hideous Strength, p. 1.